At San Diego Sports Physical Therapy your licensed & experienced physical therapists will work together with your surgeon to insure consistent communication involving post surgical progress to a full recovery. Initial focus is on modalities to reduce post surgical edema/pain while restoring range of motion and normal movement patterns.

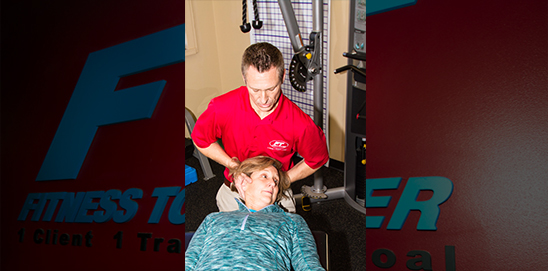

All patients will receive one to one manual therapy from our highly skilled and licensed physical therapist. Immediately following the initial evaluation of a patient, physicians will receive a full written report from the treating physical therapist. Subsequent progress notes will be sent to keep all physicians up to date on the progress of their patients.

At San Diego Sports Physical Therapy we appreciate the trust that our referring physicians place upon us. We also acknowledge that our patients have chosen us for a reason and we aim to overdeliver in all aspects of post surgical and non-surgical rehabilitation. We achieve this by getting predictable and consistent results with cutting edge therapy methods and evidence based practices. Our continual innovation and an unequalled environment create an incredible experience that other physical therapy practices only try to replicate. The greatest compliment we receive is our competition trying to model our success.

For your education below is a protocol for just one common post surgical condition we see often at San Diego Sports Physical Therapy: a complete list of other Orthopedic/Surgical Conditions can be found by Clicking Here

Rotator Cuff Repair and Rehabilitation h6. Surgical Indications and Considerations

Anatomical Considerations: The rotator cuff “complex” is comprised of four tendons from four muscles: supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor, and subscapularis, all originating from the scapula and attaching to the tuberosities of the humerus. The supraspinatus tendon lies superiorly along the scapula and under the coracoacromial arch of the scapula and has a hypovascular zone near its insertion. The primary function of the rotator cuff is to rotate and stabilize the humeral head in the glenoid socket against the upward pull of the deltoid with overhead activities.

Pathogenesis: The supraspinatus tendon is the most commonly affected tendon in rotator cuff tears. An acute tear may occur in the case of a traumatic event to the shoulder, but more typically the tear occurs in progressive stages arising from glenohumeral instability and scapulothoracic dysfunction.

Also playing a role is the natural aging process of gradual deterioration of tendon strength and flexibility, decreased use and vascularization, along with postural changes. A combination of any of these factors leads to an impingement problem in which the tendon is compressed between the acromion and the humeral head.

These are generally classified as chronic tears, referring to repetitive microtrauma to the tendon which leads to inflammation, tendonitis, fibrosis, bone spurs, and eventually a partial thickness to complete tear. Complete tears are classified based on their size in square centimeters: small (0 – 1 cm²), medium (1 – 3 cm²), large (3 – 5 cm²), or massive (>5 cm²). Congenital bony abnormalities in which the acromion, coracoid, or greater tuberosity is thicker or protrudes into the subacromial space will also predispose a person to an impingement problem that eventually follows the same progressive course to a tear.

Epidemiology: Rotator cuff tears are more often seen in individuals who perform frequent overhead lifting or reaching activities as well as athletes such as pitchers, swimmers, and tennis players who perform repetitive overhead activities. These activities cause fatigue and subsequent weakness in the rotator cuff muscles allowing superior and anterior migration of the humeral head, and also weakness of the scapular stabilizers creating a secondary cause of an impingement. A spontaneous tear may occur after a sudden movement or impact, and is seen in 80% of patients older than 60 years when a humeral head dislocation is involved.

Diagnosis:

- Some evidence of atrophy may be seen in the supraspinatus fossa.

- Possible atrophy in the infraspinatus fossa also, depending on size of tear

- Passive motion usually maintained, but may be associated with subacromial crepitus. However, if the injury is chronic, and the patient has been avoiding using the shoulder, adhesive capsulitis may be present

- Active motion is diminished, particularly abduction, and symptoms are reproduced when the arm is lowered from an overhead position. Loss of active external rotation present in massive tears

- Muscle weakness is related to the size of the tear and muscles involved

- Neer and Hawkins Impingement Signs may be positive, but are nonspecific because they may be positive with other conditions as well (such as rotator cuff tendonitis or bursitis)

- A subacromial injection of lidocaine would improve pain, but weakness would still be present

- It is important to rule out other potential etiologies such as patients with C5-6 radiculopathy as these patients may also have an insidious onset of shoulder pain, rotator cuff weakness, and similar muscular atrophy

- A “trauma shoulder series” of plain radiographs may show superior humeral migration and degenerative conditions or bone collapse.

- An MRI may help demonstrate the size and degree of retraction of a tear.

Non-operative versus Operative Management: Surgical repair is indicated for patients who do not respond well to conservative treatment, active patients younger than 50 years with a full-thickness tear, or who have an acute tearing of a chronic injury. Conservative management will include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), cortisone injections, heat, ice, rest, and rehabilitation programs.

The goals are to first restore normal range of motion, then strengthen the rotator cuff initially below shoulder level and gradually increase resistance to all functional planes and range of motion without aggravating symptoms. Normalizing scapulothoracic and glenohumeral rhythm may also be included.

Approximately 50% of patients with rotator cuff tears improve to their satisfaction within 4 to 6 months of this treatment, but these results can deteriorate with time. Patients who do not progress, have pain even after regaining strength, or have significant weakness or posterior cuff involvement may also benefit from earlier surgery rather than waiting through the 4 to 6 month period of conservative treatment. This is particularly the case with younger patients with higher functional demands.

Surgical Procedure: The primary goal of surgery is elimination or significant reduction of pain. Other goals are to improve shoulder range of motion, strength, and function. Surgical repair can be performed arthroscopically, partially open, or completely open. The type of procedure will depend on the size, type, and pattern of the tear as well as the surgeon’s preference.

Generally the larger tears (3 to 5 cm) require more open techniques than the smaller tears (3 cm or less). Along with repair of the rotator cuff operative procedures also typically include an anteroinferior acromioplasty to decompress the subacromial space. The cuff tear is repaired using permanent sutures to the greater tuberosity with the goal of having minimal tension with the arm positioned at the side.

A double layer fixation technique has been shown to provide greater initial fixation strength than single layer fixation. This is critical as the occurrence of rotator cuff repair failure is highest in the early postoperative phase before there has been time for sufficient tendon-to-bone healing. Clinical results for pain relief are satisfactory 85% to 95% of the time.

This appears to correlate with the sufficiency of the acromioplasty and subacromial decompression. The integrity of the cuff repair, preoperative size of the tear, and quality of the tendon tissue influence the functional outcome. Acute tears with early repair may have a slightly greater susceptibility to develop stiffness, but it has also been noted that these patients progress with rehabilitation more rapidly than those with late repair.

Loma Linda University and University of Pacific Doctorate in Physical Therapy Programs Joe Godges DPT, MA, OCS